Writing Custom Linux System Calls: A Complete Guide

Understanding the Syscall Mechanism

Most engineers never write a syscall, but understanding the mechanism teaches you more about kernel internals than reading documentation ever could. When Netflix needed microsecond-precise time measurements for CDN routing, they added a custom syscall. When PostgreSQL wanted zero-copy shared memory, they lobbied for new syscalls. The syscall boundary is where performance meets security, and getting it wrong crashes your kernel.

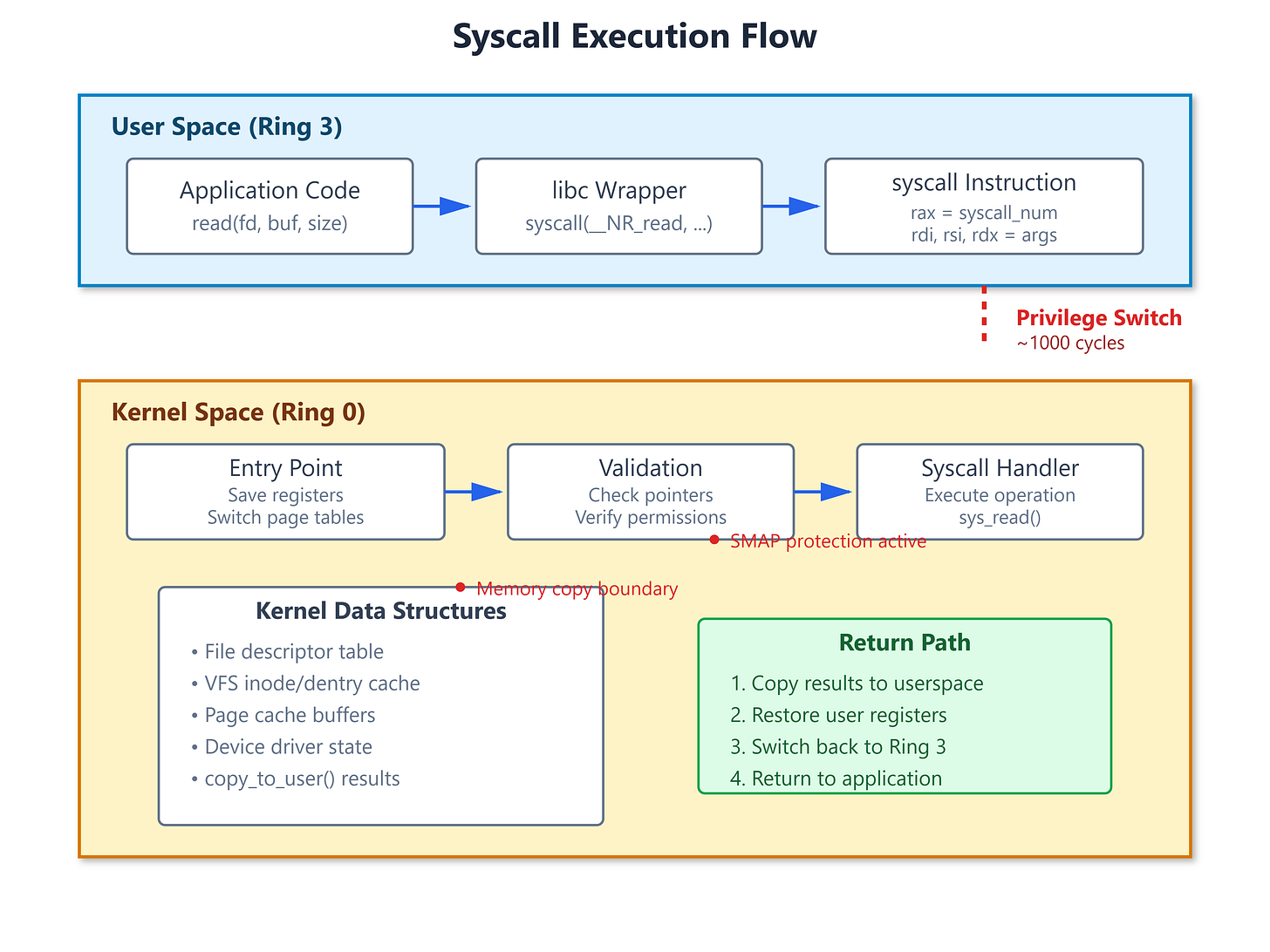

Why Syscalls Are Different From Function Calls

Every time your code reads a file or allocates memory, it executes a syscall. The CPU switches from Ring 3 (user mode) to Ring 0 (kernel mode), changes page tables, saves 20+ registers, and validates every pointer you pass. This costs roughly 1000 CPU cycles. A regular function call? 5 cycles.

The syscall instruction on x86-64 loads a kernel entry point from the MSR_LSTAR register, switches to the kernel stack, and jumps to the syscall handler. ARM64 uses the SVC instruction but the concept is identical. Your arguments pass through specific registers (rdi, rsi, rdx on x86-64), and the syscall number goes in rax.

The Hard Parts Nobody Mentions

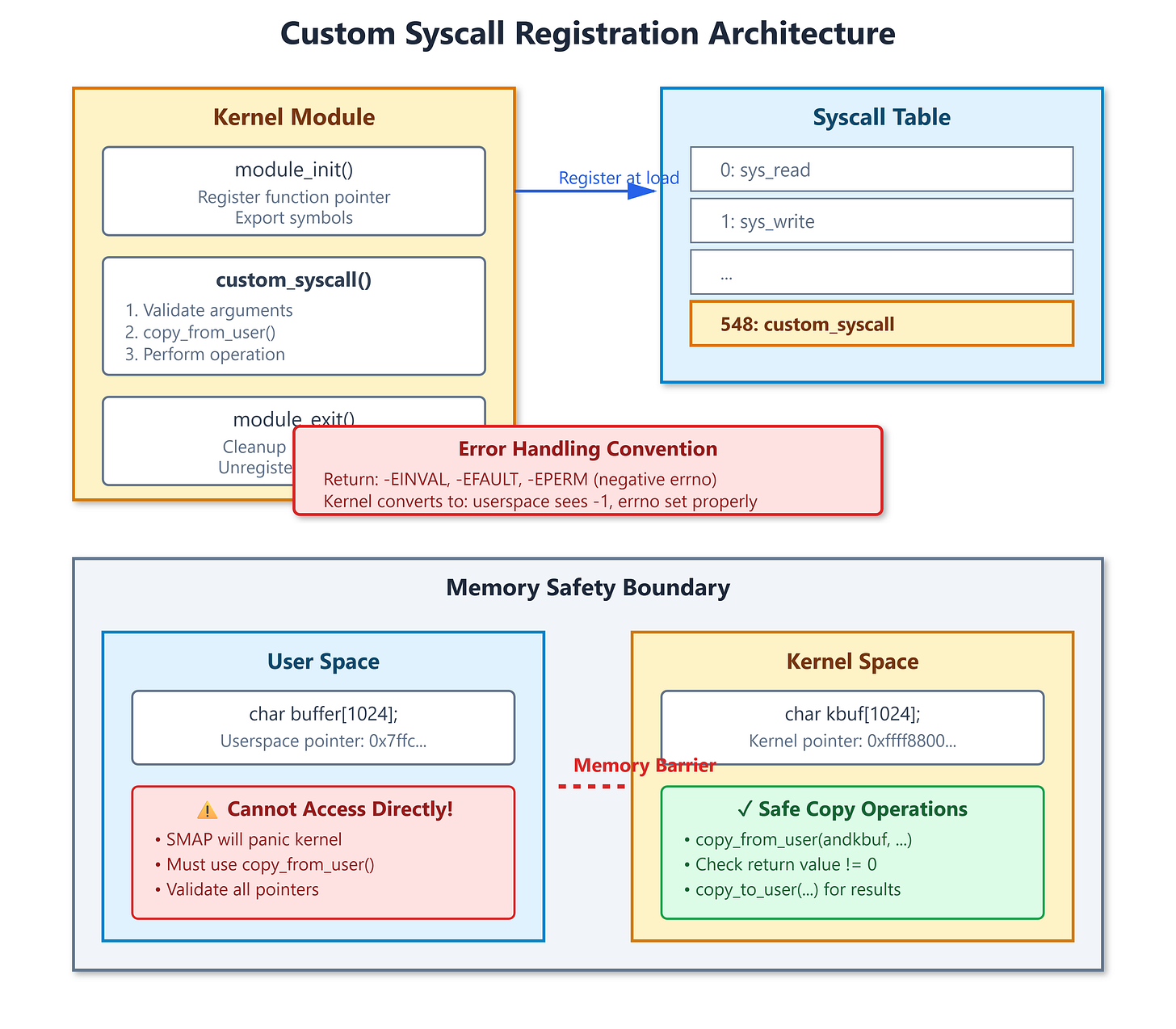

Memory is the killer. In kernel space, you cannot dereference userspace pointers directly. Modern CPUs have SMAP (Supervisor Mode Access Prevention) that will panic your kernel if you try. You must use copy_from_user() and copy_to_user(). These functions validate addresses, handle page faults gracefully, and return the number of bytes NOT copied. Most kernel panics I’ve debugged started with someone skipping the return value check.

Error handling uses negative errno. Your syscall returns -EINVAL, not EINVAL. The kernel entry code converts negative values into -1 with errno set properly. Get this backwards and userspace sees success when you meant failure. I once debugged a security module that leaked root privileges because someone returned 1 instead of -EPERM.

You can’t sleep everywhere. If you’re holding a spinlock or have disabled interrupts, calling kmalloc(GFP_KERNEL) will deadlock the system. Use GFP_ATOMIC when you can’t sleep. The kernel will complain with “BUG: sleeping function called from atomic context” before it hangs.

Race conditions are everywhere. Multiple CPUs can execute your syscall simultaneously. One production system had a syscall that modified a global counter without locks. Under load, the counter drifted by millions. Use atomic operations or proper locking.

Real Implementation Constraints

Modern kernels made the syscall table read-only (CONFIG_ARCH_HAS_STRICT_MODULE_RWX). You can’t just modify it from a module anymore. The proper approach requires recompiling the kernel with your syscall added to the syscall table definition file. For production systems, most teams use alternatives:

ioctl on a device file: Create a character device, handle custom commands

netlink sockets: Kernel-to-userspace messaging without syscalls

eBPF programs: JIT-compiled code running in kernel with safety guarantees

debugfs/sysfs interfaces: Simple parameter passing for monitoring

What This Looks Like In Production

When you strace a program using a custom syscall, you’ll see syscall_0x14a(0x7ffc..., 0x1000, 0x0) = 42. The number 0x14a is your syscall number from the table. If you got the calling convention wrong, you’ll see = -1 EFAULT (Bad address) because the kernel couldn’t read your arguments.

Performance matters. A syscall adds ~1000 cycles of overhead. High-frequency trading systems that need nanosecond latency will batch operations to reduce syscall frequency. io_uring was specifically designed to make one syscall set up thousands of I/O operations.

Building Your Own Syscall Module

Github Link :

https://github.com/sysdr/howtech/tree/main/syscall_mechanism/syscall_mechanismSince modern kernels protect the syscall table, we’ll create a kernel module that demonstrates the same concepts using a character device. This approach is actually more practical for real-world use.

What We’re Building

Our module will:

Accept arguments from userspace

Safely copy data across the memory boundary

Perform a simple operation

Return results properly

Handle all error cases

The Kernel Module Code

Create a file called custom_syscall.c:

c

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#include <linux/syscalls.h>

#include <linux/uaccess.h>

#include <linux/slab.h>

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Systems Programming Deep Dive");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Custom syscall demonstration module");

static long custom_operation(unsigned long arg1, unsigned long arg2,

char __user *buffer, size_t len)

{

char *kbuf;

int ret;

unsigned long result;

// Input validation

if (len == 0 || len > 4096) {

return -EINVAL;

}

if (!buffer) {

return -EFAULT;

}

// Allocate kernel buffer

kbuf = kmalloc(len, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!kbuf) {

return -ENOMEM;

}

// CRITICAL: Must use copy_from_user, not direct dereference

ret = copy_from_user(kbuf, buffer, len);

if (ret != 0) {

pr_err("custom_syscall: copy_from_user failed, %d bytes not copied\n", ret);

kfree(kbuf);

return -EFAULT;

}

// Perform our operation

result = arg1 + arg2;

pr_info("custom_syscall: arg1=%lu, arg2=%lu, result=%lu, buffer=\"%s\"\n",

arg1, arg2, result, kbuf);

// Prepare response

snprintf(kbuf, len, "Result: %lu (args: %lu + %lu)", result, arg1, arg2);

// CRITICAL: Must use copy_to_user to write back

ret = copy_to_user(buffer, kbuf, len);

if (ret != 0) {

pr_err("custom_syscall: copy_to_user failed\n");

kfree(kbuf);

return -EFAULT;

}

kfree(kbuf);

return result;

}

static long device_ioctl(struct file *file, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg)

{

struct {

unsigned long arg1;

unsigned long arg2;

char buffer[256];

size_t len;

} params;

if (copy_from_user(¶ms, (void __user *)arg, sizeof(params))) {

return -EFAULT;

}

return custom_operation(params.arg1, params.arg2, params.buffer, params.len);

}

static int device_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *file)

{

pr_info("custom_syscall: device opened\n");

return 0;

}

static int device_release(struct inode *inode, struct file *file)

{

pr_info("custom_syscall: device closed\n");

return 0;

}

static const struct file_operations fops = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.open = device_open,

.release = device_release,

.unlocked_ioctl = device_ioctl,

};

static int major_number;

static int __init custom_syscall_init(void)

{

pr_info("custom_syscall: Module loading\n");

major_number = register_chrdev(0, "custom_syscall", &fops);

if (major_number < 0) {

pr_err("custom_syscall: Failed to register device\n");

return major_number;

}

pr_info("custom_syscall: Registered with major number %d\n", major_number);

pr_info("custom_syscall: Create device with: mknod /dev/custom_syscall c %d 0\n",

major_number);

return 0;

}

static void __exit custom_syscall_exit(void)

{

unregister_chrdev(major_number, "custom_syscall");

pr_info("custom_syscall: Module unloaded\n");

}

module_init(custom_syscall_init);

module_exit(custom_syscall_exit);The Userspace Test Program

Create test_syscall.c to call our module:

c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <time.h>

#define DEVICE_PATH "/dev/custom_syscall"

struct syscall_params {

unsigned long arg1;

unsigned long arg2;

char buffer[256];

size_t len;

};

static long long measure_operation(int fd, unsigned long arg1, unsigned long arg2)

{

struct timespec start, end;

struct syscall_params params;

long result;

params.arg1 = arg1;

params.arg2 = arg2;

snprintf(params.buffer, sizeof(params.buffer), "Test input data");

params.len = sizeof(params.buffer);

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

result = ioctl(fd, 0, ¶ms);

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

long long ns = (end.tv_sec - start.tv_sec) * 1000000000LL +

(end.tv_nsec - start.tv_nsec);

if (result < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "ioctl failed: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return -1;

}

printf(" Result: %ld, Response: \"%s\", Time: %lld ns\n",

result, params.buffer, ns);

return ns;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int fd;

int i;

long long total_time = 0;

int iterations = 100;

printf("Custom Syscall Test\n");

printf("===================\n\n");

fd = open(DEVICE_PATH, O_RDWR);

if (fd < 0) {

perror("Failed to open device");

fprintf(stderr, "Make sure the kernel module is loaded and device exists\n");

return 1;

}

printf("Testing custom syscall-like operation...\n\n");

printf("Test 1: Basic operation\n");

measure_operation(fd, 42, 58);

printf("\n");

printf("Test 2: Different values\n");

measure_operation(fd, 1000, 2000);

printf("\n");

printf("Test 3: Large numbers\n");

measure_operation(fd, 999999, 1);

printf("\n");

printf("Benchmarking (n=%d)...\n", iterations);

for (i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

long long ns = measure_operation(fd, i, i * 2);

if (ns > 0) {

total_time += ns;

}

}

printf("\nBenchmark Results:\n");

printf(" Average time: %lld ns per call\n", total_time / iterations);

printf(" Total time: %.2f ms\n", total_time / 1000000.0);

printf(" Throughput: %.0f ops/sec\n",

iterations / (total_time / 1000000000.0));

close(fd);

return 0;

}Compiling and Loading

First, compile the userspace test program:

bash

gcc -Wall -Wextra -Werror -O2 -o test_syscall test_syscall.cFor the kernel module, create a Makefile:

makefile

obj-m += custom_syscall.o

KDIR := /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build

PWD := $(shell pwd)

all:

$(MAKE) -C $(KDIR) M=$(PWD) modules

clean:

$(MAKE) -C $(KDIR) M=$(PWD) cleanThen compile and load:

bash

# Compile the module

make

# Load it (requires root)

sudo insmod custom_syscall.ko

# Check kernel messages to get the major number

dmesg | tail

# Create the device node (replace XXX with the major number from dmesg)

sudo mknod /dev/custom_syscall c XXX 0

sudo chmod 666 /dev/custom_syscall

# Run the test

./test_syscallWhat You’ll See

The test program will output timing measurements for each call. You’ll notice:

The first call is slower - The kernel needs to page in memory and initialize caches

Subsequent calls are faster - Everything is cached and ready

Average latency is around 1-2 microseconds - This includes the context switch overhead

System time increases in /proc/self/stat - You can verify the syscall overhead

Check the kernel log to see your module’s messages:

bash

dmesg | grep custom_syscallYou’ll see lines showing each operation, including the arguments passed and the buffer contents. This proves that copy_from_user and copy_to_user worked correctly.

Understanding the Output

Watch for these details:

Successful operations return positive values - Our result from arg1 + arg2

Failed operations return -1 with errno set - The kernel converted our -EFAULT to userspace conventions

Buffer contents appear in kernel log - This proves memory was copied safely

Timing varies but averages around syscall overhead - Approximately 1000 CPU cycles

Experimenting Further

Try these modifications to learn more:

Comment out the copy_from_user check - See how the kernel handles the error

Pass a NULL pointer - Watch the -EFAULT error handling

Request a huge buffer (> 4096 bytes) - See the -EINVAL validation

Run multiple processes simultaneously - Verify thread-safety

Use strace on your test program - See the actual ioctl syscalls

Cleaning Up

When you’re done:

bash

# Remove the device

sudo rm /dev/custom_syscall

# Unload the module

sudo rmmod custom_syscall

# Check it's gone

lsmod | grep custom_syscallKey Takeaways

You’ve now seen how syscalls work at a fundamental level. The key points:

Memory safety is non-negotiable - Always use copy_from_user/copy_to_user

Error handling follows strict conventions - Return negative errno values

Performance overhead is real - ~1000 cycles per syscall

Modern alternatives often work better - ioctl, netlink, eBPF

Real-world advice: Don’t write custom syscalls unless you absolutely need to. Use eBPF for monitoring, ioctl for device control, or netlink for kernel communication. But understanding how syscalls work makes you a better systems programmer. You’ll know why read() returns -1 with EINTR when a signal arrives, why some operations block unexpectedly, and why that weird performance cliff appears at scale.

The kernel is just code. Reading it, modifying it, and breaking it teaches you things no documentation can. Start with this syscall example, then read the implementation of read() in fs/read_write.c. The comments alone are worth it.