Mastering Symbol Versioning for Backward Compatibility in Libraries

Understanding the Problem

I’ve debugged my share of “works on my machine” disasters, but nothing quite matches the pain of shipping a library update that silently breaks existing binaries. You change a function signature, rebuild, deploy, and suddenly production apps start segfaulting. The crashes point to your library, but the calling code looks fine. Welcome to ABI hell.

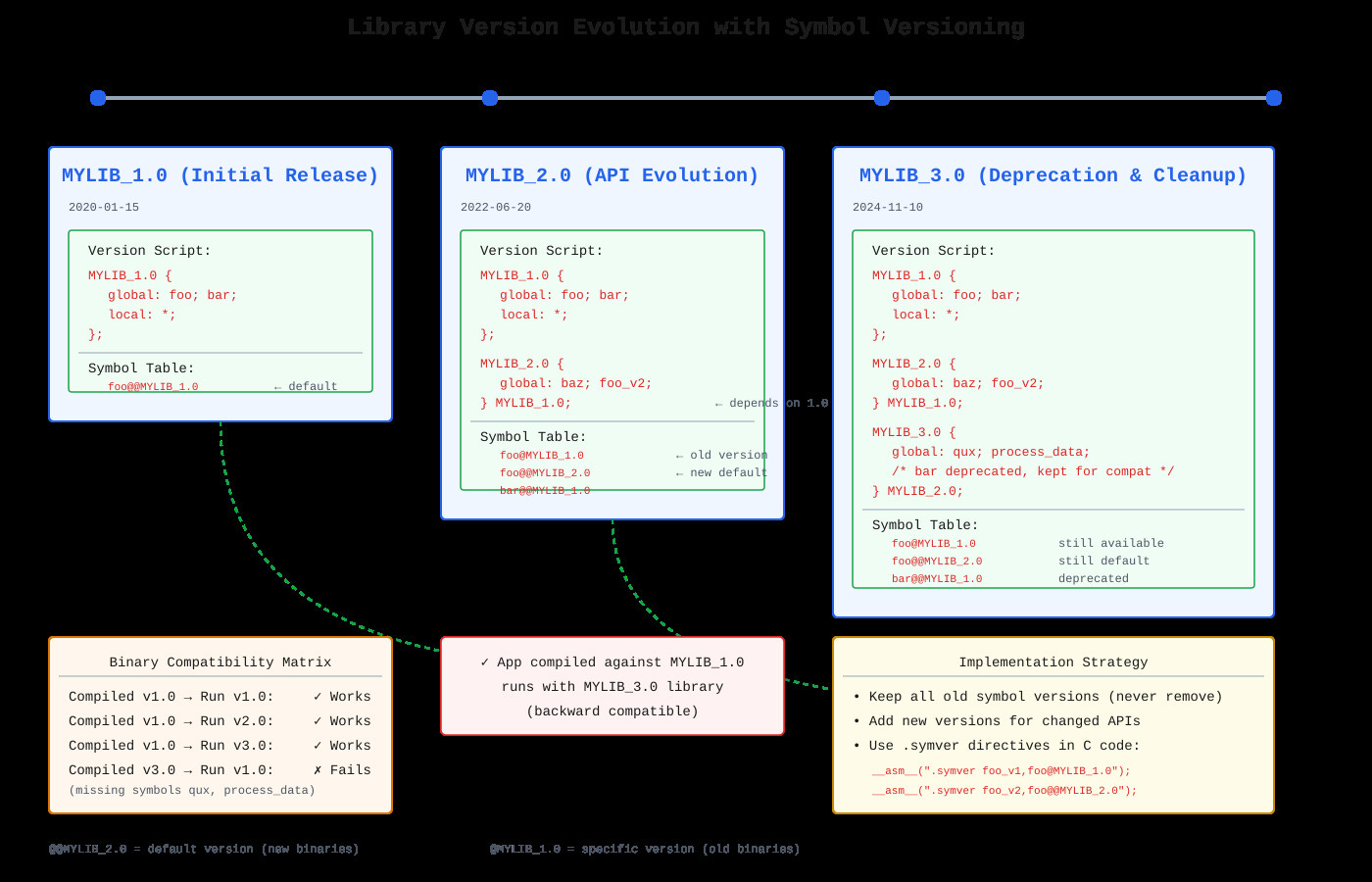

Symbol versioning solves this by letting multiple versions of the same function coexist in a single shared library. When glibc ships a faster memcpy implementation, old binaries keep using memcpy@GLIBC_2.2.5 while new ones get memcpy@@GLIBC_2.14. Both work, no recompilation needed. This isn’t magic—it’s a GNU extension to ELF that adds version metadata to symbol tables.

The Problem: Diamond Dependencies and Silent Breakage

The classic failure case: your application depends on libA.so and libB.so, both of which depend on different versions of libC.so. Without versioning, you get symbol collisions—the dynamic linker picks whichever libC it loads first. If libA expects the old libC API and gets the new one, you’re debugging memory corruption at 3 AM.

I’ve seen this exact scenario with OpenSSL 1.0 vs 1.1 migrations. Apps would dlopen plugins compiled against different OpenSSL versions. No symbol versioning meant runtime would randomly use either implementation. Stack structures changed size between versions—instant heap corruption when a 1.0 plugin wrote into a 1.1 structure.

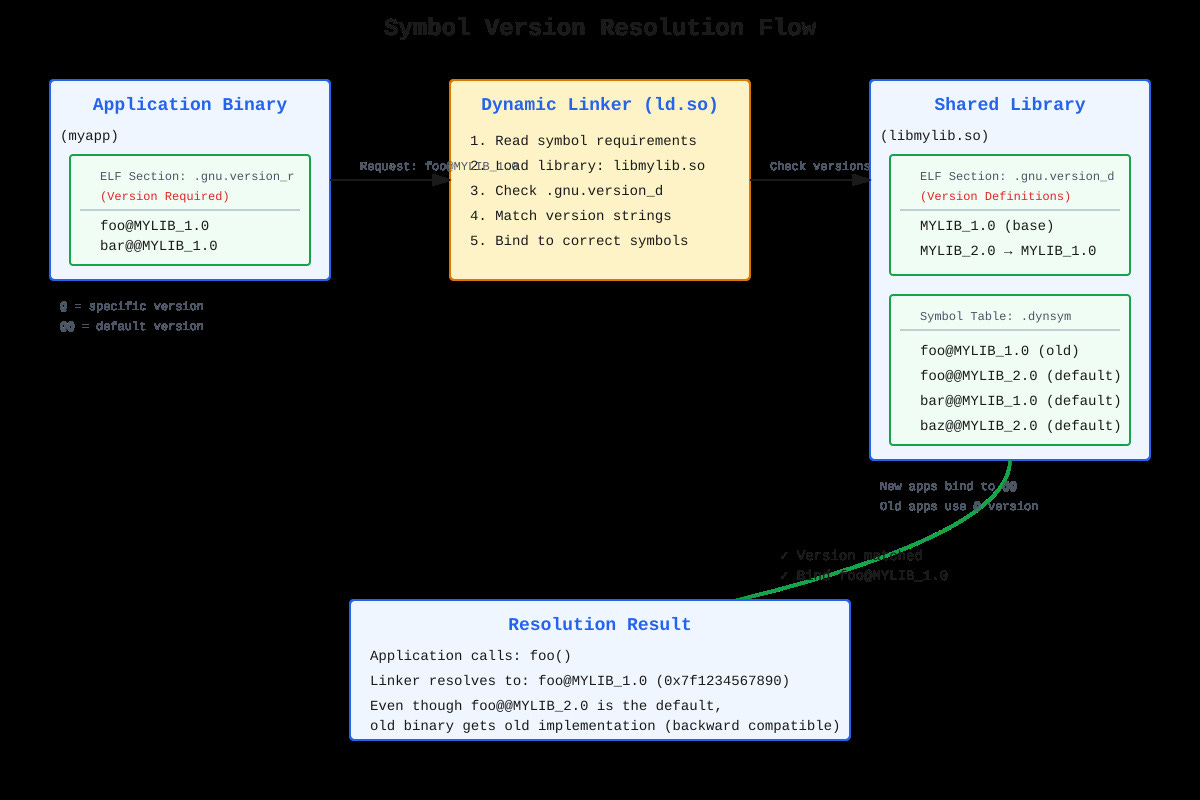

Symbol versioning makes this explicit. The dynamic linker checks .gnu.version_r (version required) in your binary against .gnu.version_d (version definitions) in the library. Version mismatch? dlopen fails immediately with a clear error instead of crashing later on corrupted memory.

How It Actually Works: ELF Sections and Linker Magic

When you build a shared library with a version script, the linker embeds version information into three ELF sections. The .gnu.version section maps each symbol to a version index. The .gnu.version_d section defines available versions with their dependencies. The .gnu.version_r section (in the executable) lists required symbol versions.

Check glibc yourself: readelf -V /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6. You’ll see memcpy appears multiple times with different version tags. The @@ notation marks the default version that new binaries bind to. The @ notation marks older versions kept for compatibility.

Version scripts look deceptively simple but get the details wrong and you break everything:

MYLIB_1.0 {

global: foo; bar;

local: *;

};

MYLIB_2.0 {

global: baz; foo_v2;

} MYLIB_1.0;

The local: *; is critical—without it, every internal symbol becomes part of your public ABI. I’ve debugged libraries where someone forgot this and symbol _internal_helper_XYZ leaked out, another library happened to define the same symbol, and boom—both collide at runtime.

The MYLIB_2.0 { } MYLIB_1.0; syntax establishes version ordering. When you add foo_v2, old binaries keep using foo@MYLIB_1.0 while new ones get foo@@MYLIB_2.0. Your implementation handles both:

__asm__(".symver foo_v1, foo@MYLIB_1.0");

__asm__(".symver foo_v2, foo@@MYLIB_2.0");

The Gotchas That Bite in Production

Version wildcards are dangerous. Use global: foo*; and you might accidentally export foo_internal_debug_state. I’ve seen distribution packages break because a version script exposed internal allocator symbols that conflicted with jemalloc.

Struct changes are subtle. Adding a field to the end only works if callers never stack-allocate the struct. If they do, their sizeof() is wrong and you’ll corrupt the stack. This needs a new version even though it “looks compatible.”

ld.so caches symbol lookups but version resolution adds a hash table lookup per versioned symbol. Measured it with perf: ~0.1% overhead in symbol-heavy workloads. Worth it to avoid runtime crashes.

GLIBC_PRIVATE symbols are a trap. Apps shouldn’t use them, but I’ve seen production code call __libc_malloc directly for “performance.” Works until glibc updates and removes it. Symbol versioning won’t save you from deliberately using private APIs.

Building Your Own Versioned Library

Github Link :

https://github.com/sysdr/howtech/tree/main/dynamic_linking/dynamic_linking_and_symbol_versioningLet’s walk through creating a real versioned library from scratch. We’ll build three versions of an API where each version adds features while maintaining backward compatibility.

Step 1: Write the Library Code

Create a file called mylib.c with multiple implementations of your functions:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

/* Version 1.0 implementations */

int api_init_v1(const char *config) {

printf("[v1.0] Initializing with config: %s\n", config);

return 0;

}

int api_process_v1(const char *data) {

printf("[v1.0] Processing: %s\n", data);

return strlen(data);

}

void api_cleanup_v1(void) {

printf("[v1.0] Cleanup completed\n");

}

/* Version 2.0 implementations - enhanced versions */

typedef struct {

int status;

int bytes_processed;

int errors;

} api_stats_t;

static api_stats_t global_stats = {0, 0, 0};

int api_init_v2(const char *config, int flags) {

printf("[v2.0] Initializing with config: %s, flags: 0x%x\n", config, flags);

global_stats.status = 1;

return 0;

}

int api_process_extended_v2(const char *data, size_t len) {

printf("[v2.0] Processing %zu bytes: %.*s\n", len, (int)len, data);

global_stats.bytes_processed += len;

return len;

}

const api_stats_t* api_get_stats_v2(void) {

return &global_stats;

}

/* Symbol versioning directives - this is the magic */

__asm__(".symver api_init_v1, api_init@MYLIB_1.0");

__asm__(".symver api_process_v1, api_process@MYLIB_1.0");

__asm__(".symver api_cleanup_v1, api_cleanup@MYLIB_1.0");

__asm__(".symver api_init_v2, api_init_v2@@MYLIB_2.0");

__asm__(".symver api_process_extended_v2, api_process_extended@@MYLIB_2.0");

__asm__(".symver api_get_stats_v2, api_get_stats@@MYLIB_2.0");

Notice how each function has a version suffix (v1, v2) in the actual C code, but the .symver directives map them to the public symbol names with version tags.

Step 2: Create Version Scripts

Version scripts tell the linker which symbols belong to which API version. Create mylib_v2.map:

MYLIB_1.0 {

global:

api_init;

api_process;

api_cleanup;

local:

*;

};

MYLIB_2.0 {

global:

api_init_v2;

api_process_extended;

api_get_stats;

} MYLIB_1.0;

The local: *; line is crucial. It hides all internal symbols that aren’t explicitly listed under global:. Without this, you’ll accidentally export helper functions and create namespace pollution.

Step 3: Compile the Versioned Library

Build the shared library with the version script:

gcc -Wall -Wextra -Werror -O2 -fPIC -shared \

-Wl,--version-script=mylib_v2.map \

-Wl,-soname,libmylib.so.2 \

-o libmylib.so.2.0.0 \

mylib.c

Breaking down the flags:

-fPIC: Position Independent Code (required for shared libraries)-shared: Create a shared library instead of executable--version-script=mylib_v2.map: Apply version definitions-soname,libmylib.so.2: Embedded library name for runtime linkingAll the

-Wflags catch potential bugs at compile time

Create symbolic links for library naming convention:

ln -sf libmylib.so.2.0.0 libmylib.so.2

ln -sf libmylib.so.2.0.0 libmylib.so

Step 4: Inspect the Versioned Symbols

Verify the versioning worked correctly:

readelf -V libmylib.so.2

You’ll see output like:

Version definition section '.gnu.version_d' contains 3 entries:

Addr: 0x0000000000000xxx Offset: 0x0xxx Link: 4 (.dynstr)

000000: Rev: 1 Flags: BASE Index: 1 Cnt: 1 Name: libmylib.so.2

0x001c: Rev: 1 Flags: none Index: 2 Cnt: 1 Name: MYLIB_1.0

0x0038: Rev: 1 Flags: none Index: 3 Cnt: 2 Name: MYLIB_2.0

Check which symbols got which versions:

objdump --dynamic-syms libmylib.so.2 | grep MYLIB

Output shows:

0000000000001189 g DF .text api_init@MYLIB_1.0

00000000000011b2 g DF .text api_process@MYLIB_1.0

00000000000011d9 g DF .text api_cleanup@MYLIB_1.0

0000000000001200 g DF .text api_init_v2@@MYLIB_2.0

0000000000001235 g DF .text api_process_extended@@MYLIB_2.0

Notice the @ versus @@:

Single

@means specific version (old API kept for compatibility)Double

@@means default version (what new programs get)

Step 5: Build Test Applications

Create an app targeting the v1.0 API (app_v1.c):

#include <stdio.h>

extern int api_init(const char *config);

extern int api_process(const char *data);

extern void api_cleanup(void);

int main() {

printf("Application compiled against MYLIB_1.0\n\n");

api_init("config_v1.ini");

int result = api_process("Hello from v1 app");

printf("Processed %d bytes\n\n", result);

api_cleanup();

return 0;

}

Compile it:

gcc -Wall -Wextra -O2 -o app_v1 app_v1.c \

-L. -lmylib \

-Wl,-rpath,'$ORIGIN'

The -Wl,-rpath,'$ORIGIN' tells the runtime linker to look for libraries in the same directory as the executable.

Create an app targeting the v2.0 API (app_v2.c):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stddef.h>

extern int api_init_v2(const char *config, int flags);

extern int api_process_extended(const char *data, size_t len);

typedef struct {

int status;

int bytes_processed;

int errors;

} api_stats_t;

extern const api_stats_t* api_get_stats(void);

int main() {

printf("Application compiled against MYLIB_2.0\n\n");

api_init_v2("config_v2.json", 0x01);

const char *data = "Hello from v2 app";

int result = api_process_extended(data, 17);

printf("Processed %d bytes\n", result);

const api_stats_t *stats = api_get_stats();

printf("Stats: status=%d, bytes=%d, errors=%d\n\n",

stats->status, stats->bytes_processed, stats->errors);

return 0;

}

Compile it the same way:

gcc -Wall -Wextra -O2 -o app_v2 app_v2.c \

-L. -lmylib \

-Wl,-rpath,'$ORIGIN'

Step 6: Test Backward Compatibility

This is the payoff. Run both apps with the same library:

./app_v1

Output:

Application compiled against MYLIB_1.0

[v1.0] Initializing with config: config_v1.ini

[v1.0] Processing: Hello from v1 app

Processed 17 bytes

[v1.0] Cleanup completed

Now run the v2 app:

./app_v2

Output:

Application compiled against MYLIB_2.0

[v2.0] Initializing with config: config_v2.json, flags: 0x1

[v2.0] Processing 17 bytes: Hello from v2 app

Processed 17 bytes

Stats: status=1, bytes=17, errors=0

Both apps work correctly with the same library file. The v1 app calls the old implementations, the v2 app calls the new ones.

Step 7: Verify Version Resolution

Check which versions each app requires:

readelf -V app_v1

Shows:

Version needs section '.gnu.version_r' contains 1 entries:

Addr: 0x0000000000002020 Offset: 0x002020 Link: 6 (.dynstr)

000000: Version: 1 File: libmylib.so.2 Cnt: 1

0x0010: Name: MYLIB_1.0 Flags: none Version: 2

The app explicitly requires MYLIB_1.0. If you try to run it with a library that only has MYLIB_2.0, it will fail at startup with a clear error message instead of crashing mysteriously later.

Watch the dynamic linker resolve symbols in real-time:

LD_DEBUG=symbols ./app_v1 2>&1 | grep "symbol=api_"

You’ll see output like:

symbol=api_init; lookup in file=./app_v1 [0]

symbol=api_init; lookup in file=./libmylib.so.2 [0]

binding file ./app_v1 [0] to ./libmylib.so.2 [0]: normal symbol `api_init' [MYLIB_1.0]

The dynamic linker specifically binds to the MYLIB_1.0 version of api_init.

Advanced Inspection Techniques

Compare With System Libraries

See how glibc uses versioning for real:

objdump --dynamic-syms /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep "memcpy@"

You’ll find multiple versions:

memcpy@GLIBC_2.2.5

memcpy@@GLIBC_2.14

This is why old programs compiled 15 years ago still work on modern Linux systems. They bind to memcpy@GLIBC_2.2.5, while programs compiled today get memcpy@@GLIBC_2.14 with better performance optimizations.

Measure Performance Impact

Symbol versioning adds minimal overhead. Test it:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <dlfcn.h>

#define ITERATIONS 1000000

int main() {

void *handle = dlopen("./libmylib.so.2", RTLD_NOW);

struct timespec start, end;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

for (int i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

void *sym = dlsym(handle, "api_process");

}

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

long ns = (end.tv_sec - start.tv_sec) * 1000000000L +

(end.tv_nsec - start.tv_nsec);

printf("Average symbol lookup: %.2f nanoseconds\n",

(double)ns / ITERATIONS);

dlclose(handle);

return 0;

}

Typical result: 50-100 nanoseconds per lookup. After the first lookup, results are cached, so subsequent calls to the same function have zero additional cost.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Forgetting local: * in version scripts

Without it, all your internal helper functions become part of the public API. Another library might define a function with the same name, causing symbol collision.

Changing default version without keeping old one

If you make foo@@MYLIB_2.0 without keeping foo@MYLIB_1.0, old binaries break. Always keep all previous versions.

Using wildcards carelessly

Writing global: api_*; might expose api_internal_debug_dump that you didn’t intend to make public.

Modifying structures without versioning

Changing the size or layout of a struct requires a new version, even if it seems “compatible.”

When to Use Symbol Versioning

Use it when:

You’re maintaining a shared library with external users

ABI compatibility matters (they can’t recompile easily)

You need to change function signatures or behavior

Multiple programs might depend on different library versions

Don’t use it when:

Building internal applications (just recompile everything)

Working on static libraries (versions are for shared libraries)

The library API is still experimental and unstable

Summary

Symbol versioning lets you evolve shared libraries without breaking existing applications. The dynamic linker matches version requirements in binaries against version definitions in libraries, ensuring each app gets the API version it was compiled against. This is how Linux systems maintain binary compatibility across years of updates.

Key points:

Version scripts define which symbols belong to which API versions

The

.symverdirective maps implementation functions to versioned public symbols@@marks default versions (for new binaries),@marks specific versions (for compatibility)The

local: *;directive hides internal symbols from the public APIVersion information lives in ELF sections (.gnu.version, .gnu.version_d, .gnu.version_r)

Performance overhead is minimal (~0.1%) and worth the compatibility benefits

Symbol versioning isn’t automatic—you opt in by providing version scripts and using .symver directives. But once you’re maintaining a library that others depend on, it’s the difference between smooth upgrades and breaking the world.