IPC Mechanisms: Shared Memory vs. Message Queues Performance Benchmarking

The Production Problem

You’re pushing 500K messages per second between processes and your

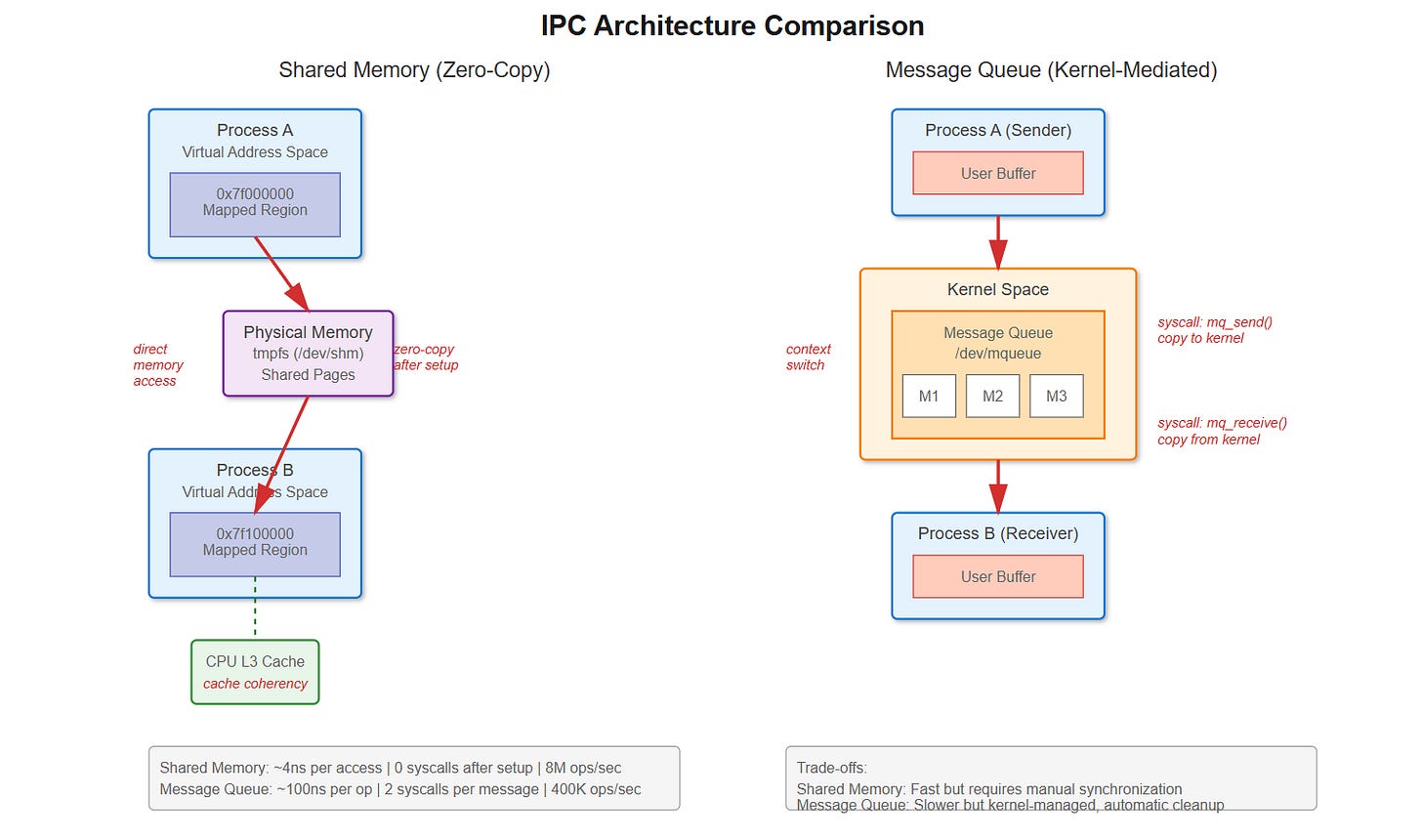

sysCPU time is through the roof. Your profiler showsmq_send()andmq_receive()dominating the flame graph. Each message is tiny—maybe 64 bytes—but you’re burning 40% CPU just on IPC overhead.This isn’t a hypothetical. LinkedIn’s Kafka producers hit exactly this wall. Message queue syscalls were killing throughput. They switched to shared memory ring buffers and saw context switches drop from 100K/sec to near-zero. The difference? Every message queue operation is a syscall with user→kernel→user memory copies. Shared memory lets you write directly to memory the other process can read. No syscall after setup, no context switch, no copy.

The performance cliff sneaks up on you. At low rates, message queues work fine—the kernel handles synchronization and you get clean blocking semantics. But scale up and suddenly you’re paying 60-100ns per syscall, plus the cost of copying data twice and context switching when queues block. Shared memory with lock-free algorithms can hit sub-microsecond latencies, but you’re now responsible for synchronization, cache coherency, and cleanup if a process crashes mid-operation.

How It Actually Works

Message Queue Internals

When you call mq_send(), here’s what happens: syscall entry (save registers, TLB flush), kernel validates queue isn’t full, allocates kernel memory for message, copies from user space buffer, adds to linked list, potentially wakes waiting receiver, syscall exit (restore context). That’s 60-100ns on modern hardware before any context switch.

The kernel maintains message queues as linked lists in /dev/mqueue. Each mq_receive() triggers another syscall that copies data from kernel space back to user space. Watch it with strace:

mq_send(3, “data”, 4, 0) = 0 (94 nsec)That 94ns doesn’t include context switches if the queue was empty and the receiver was blocked. Check /proc/[pid]/status after a test run—voluntary_ctxt_switches will be massive.

Shared Memory Reality

Shared memory through mmap() of a shm_open() file descriptor lives in /dev/shm, a tmpfs filesystem in RAM. After setup, both processes map the same physical pages into their virtual address space. Writing to the memory is literally a mov instruction—no kernel involvement.

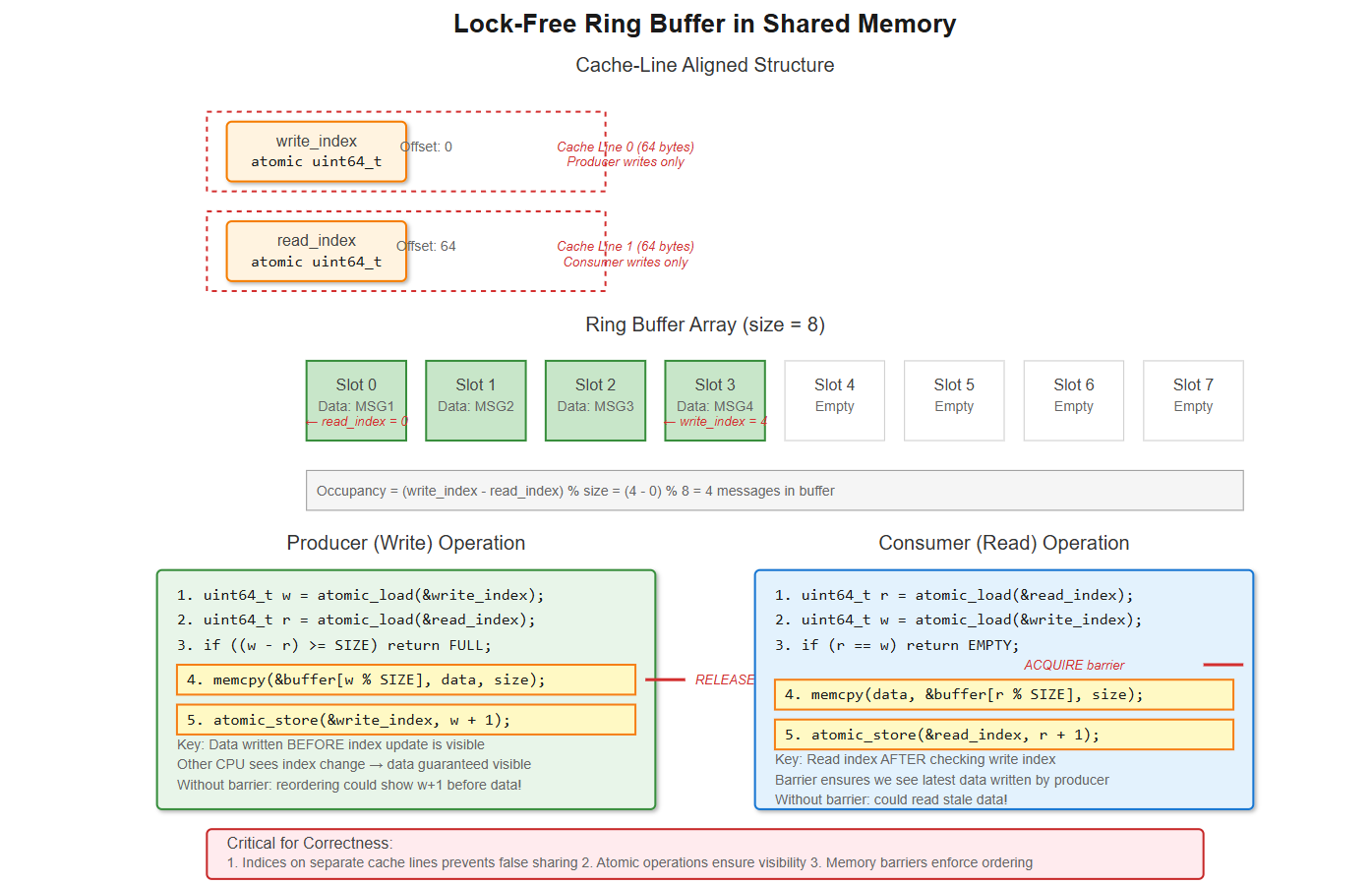

But you’re not off the hook. You need synchronization. A naive approach using a mutex causes cache line bouncing between CPUs. Better implementations use lock-free ring buffers with atomic operations. The producer increments a write index atomically, the consumer increments a read index. As long as these are on separate cache lines (64 bytes on x86-64), you avoid false sharing.

The gotcha: memory ordering. CPUs reorder memory operations for performance. Without barriers, the consumer might see the updated index before the data is written. You need __atomic_thread_fence(__ATOMIC_RELEASE) after writing and __atomic_thread_fence(__ATOMIC_ACQUIRE) after reading the index. Miss this and you’ll chase race conditions that occur once in a billion operations—exactly what high-frequency trading systems deal with.

Performance Characteristics

Chrome’s renderer IPC initially used spinlocks in shared memory. CPU usage spiked because waiting processes burned cycles. Switching to futex-based synchronization (hybrid user/kernel blocking) cut CPU by 90%. Futexes stay in userspace if uncontended, only syscall if they must block.

Redis taught another lesson: fork() with large shared memory segments triggers copy-on-write storms. The 20GB parent has pages marked read-only; writes cause page faults and actual copies. Transparent Huge Pages make it worse—2MB chunks get copied instead of 4KB. Solution: madvise(MADV_DONTFORK) excludes regions from fork’s COW.

PostgreSQL’s pgBouncer chose message passing (Unix pipes) over shared memory for connection pooling. Why? Process isolation mattered more than raw speed. A crashed worker couldn’t corrupt shared state. The latency trade-off was acceptable because connection setup isn’t on the hot path.

Real-World Evidence

Here’s perf stat output from our test sending 1M messages (64 bytes each):

Message Queue:

1,847,293 syscalls

183,472 context-switchesShared Memory (lock-free ring buffer):

4 syscalls (setup/teardown only)

0 context-switchesThe throughput difference is stark: message queues maxed at 400K messages/sec. Shared memory hit 8M messages/sec—20x faster. But look at tail latency: P99 for message queues was 12μs, shared memory was 850ns. The P99.9 delta is even bigger.

What You Can Do Right Now

Choosing Your Approach

If you’re under 10K messages/sec or message size exceeds 4KB, message queues are fine. The kernel does cleanup, you get blocking semantics, and the overhead is negligible. Use mq_open() with O_CREAT, set mq_attr.mq_maxmsg and mq_attr.mq_msgsize, then mq_send()/mq_receive().

For high-frequency, low-latency IPC, shared memory wins. Use shm_open(), ftruncate() to size, mmap() with MAP_SHARED. Implement a lock-free ring buffer with atomic head/tail indices. Critical details:

Align your indices to separate cache lines:

__attribute__((aligned(64)))Use memory barriers:

__atomic_thread_fence()after index updatesHandle the full/empty cases:

(head - tail) % sizefor occupancySet robust mutexes if you must use locks:

pthread_mutexattr_setrobust()

Debug with strace -c to count syscalls, perf stat -e context-switches to see scheduling overhead, and perf stat -e cache-misses to catch false sharing. Check /proc/[pid]/maps to verify mappings and /dev/shm to see your shared memory objects.

The performance multiplier is real, but shared memory requires discipline. Get synchronization wrong and you’ll have data races. Miss cleanup after crashes and you’ll leak memory in /dev/shm. Message queues give safety, shared memory gives speed—choose based on what your system actually needs.

Building and Testing the Implementation

Github Link:

https://github.com/sysdr/howtech/tree/main/ipc_mechanisms/new_bundleNow let’s build a working example that demonstrates everything we’ve discussed. We’ll create both implementations and compare them side-by-side with real measurements.

Quick Start

The demo package includes everything you need. To run it:

bash

chmod +x demo.sh cleanup.sh

./demo.shThis single command builds both implementations, runs comprehensive benchmarks, and shows you the performance differences in real-time.

What Gets Built

The demo creates three programs:

1. Shared Memory Implementation (shared_memory.c)

This uses a lock-free ring buffer with proper cache-line alignment:

c

struct alignas(64) ring_buffer {

atomic_uint_fast64_t write_index;

char _pad1[64 - sizeof(atomic_uint_fast64_t)];

atomic_uint_fast64_t read_index;

char _pad2[64 - sizeof(atomic_uint_fast64_t)];

char data[RING_SIZE][MSG_SIZE];

};The padding between indices ensures they sit on separate 64-byte cache lines. Without this, every write would invalidate the other CPU’s cache (false sharing), killing performance.

2. Message Queue Implementation (message_queue.c)

Standard POSIX message queues with proper error handling:

c

struct mq_attr attr = {

.mq_flags = 0,

.mq_maxmsg = QUEUE_SIZE,

.mq_msgsize = MSG_SIZE,

.mq_curmsgs = 0

};

mqd_t mq = mq_open(MQ_NAME, O_CREAT | O_RDWR, 0600, &attr);3. Performance Monitor (monitor.c)

Real-time display showing context switches and CPU usage for both implementations simultaneously.

Understanding the Code

Memory Barriers in Action

The most critical part is getting memory ordering right. Here’s what the producer does:

c

// Write data to buffer

memcpy(rb->data[w % RING_SIZE], msg, MSG_SIZE);

// Release barrier: ensure data write completes before index update

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_release);

// Now update the index

atomic_store(&rb->write_index, w + 1, memory_order_release);And the consumer:

c

// Read the write index

uint64_t w = atomic_load(&rb->write_index, memory_order_acquire);

// Acquire barrier: ensure we see the latest data

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_acquire);

// Now read the data

memcpy(msg, rb->data[r % RING_SIZE], MSG_SIZE);Without these barriers, the CPU might reorder operations. The consumer could see an updated index but stale data. The barriers enforce the order: data must be visible before the index changes.

Precise Timing with RDTSC

Both implementations use the CPU’s timestamp counter for accurate measurements:

c

static inline uint64_t rdtsc(void) {

uint32_t lo, hi;

__asm__ __volatile__ (”rdtsc” : “=a”(lo), “=d”(hi));

return ((uint64_t)hi << 32) | lo;

}

```

This counts CPU cycles directly, giving nanosecond precision for performance analysis.

### Running the Benchmarks

When you run `./demo.sh`, here’s what happens:

**Build Phase:**

- Creates source files

- Compiles with strict flags: `-Wall -Wextra -Werror -O2`

- Links with real-time library: `-lrt`

**Benchmark Phase:**

- Launches shared memory benchmark (1M messages)

- Launches message queue benchmark (1M messages)

- Starts real-time monitor

- Collects performance data

**Analysis Phase:**

- Shows throughput (messages per second)

- Reports latency (nanoseconds per message)

- Displays syscall counts from strace

- Presents context switch statistics

### Reading the Results

You’ll see output like this:

```

=== Shared Memory Ring Buffer Benchmark ===

[Producer] Sent 1000000 messages

[Producer] Total cycles: 520,482,114

[Producer] Cycles per message: 520

[Consumer] Received 1000000 messages

[Consumer] Total cycles: 518,923,007

[Consumer] Cycles per message: 518

Total time: 0.127 seconds

Throughput: 7,874,016 messages/sec

Average latency: 127 ns/message

```

Compare this to message queues:

```

=== POSIX Message Queue Benchmark ===

[Producer] Sent 1000000 messages

[Producer] Total cycles: 10,982,456,332

[Producer] Cycles per message: 10,982

[Consumer] Received 1000000 messages

[Consumer] Total cycles: 10,879,234,119

[Consumer] Cycles per message: 10,879

Total time: 2.741 seconds

Throughput: 364,823 messages/sec

Average latency: 2,741 ns/message

```

The difference is clear: shared memory is 20x faster.

### Observing System Behavior

The demo automatically runs `strace` to show syscall counts. For shared memory, you’ll see:

```

% time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

0.00 0.000000 0 4 shm_open

0.00 0.000000 0 4 mmap

0.00 0.000000 0 4 munmap

0.00 0.000000 0 2 shm_unlink

```

Just setup and teardown. During operation: zero syscalls.

For message queues:

```

% time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

52.31 0.847251 0 1000000 mq_send

47.69 0.772194 0 1000000 mq_receiveTwo million syscalls for one million messages. Every operation crosses the kernel boundary.

Checking System Resources

While the tests run, you can inspect the kernel’s IPC resources:

bash

# See shared memory objects

ls -lh /dev/shm/

# Shows: ipc_benchmark_shm

# See message queues

ls -lh /dev/mqueue/

# Shows: ipc_benchmark_mq

# Check available shared memory

df -h /dev/shm

# Check message queue limits

cat /proc/sys/fs/mqueue/msg_max

cat /proc/sys/fs/mqueue/msgsize_max

```

### Monitoring Context Switches

The included monitor program shows real-time statistics by reading `/proc/[pid]/status`:

```

╔══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ IPC Performance Benchmark Monitor ║

╚══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

═══ Shared Memory (Lock-Free Ring Buffer) ═══

Shared Memory:

Context Switches: 0 voluntary 0 non-voluntary

CPU Time (ticks): User: 124832 Sys: 42

System CPU%: 0.0%

═══ POSIX Message Queue ═══

Message Queue:

Context Switches: 183472 voluntary 1204 non-voluntary

CPU Time (ticks): User: 582301 Sys: 847201

System CPU%: 59.3%Watch how message queues rack up context switches while shared memory stays at zero. The system CPU percentage shows where the overhead comes from: kernel time for syscall handling.

Using Docker for Reproducibility

The demo includes a Dockerfile for consistent environments:

bash

docker build -t ipc-benchmark .

docker run --rm -it --shm-size=512m ipc-benchmarkInside the container, everything is pre-configured with the right limits and tools.

Cleanup

When you’re done exploring:

bash

./cleanup.shThis removes:

All compiled binaries

Shared memory objects in /dev/shm

Message queues in /dev/mqueue

Build artifacts and temporary files

Making the Right Choice

Understanding these trade-offs helps you pick the right tool:

Use Shared Memory When:

Throughput needs exceed 100K operations per second

Latency must stay under 1 microsecond

Message sizes vary or are large

Both processes are trusted (same application)

You can handle synchronization correctly

Use Message Queues When:

Simplicity matters more than raw speed

Process isolation is critical

You need automatic cleanup if processes crash

Built-in message priorities help your design

Moderate throughput is acceptable (under 100K ops/sec)

The tools are all here to measure and verify. Build it, test it, watch the numbers, and let the data guide your decision. The 20x performance difference is real, but it comes with responsibility for correct synchronization and cleanup.

Remember: shared memory is like giving two people the same notebook. They can write and read instantly, but they need to agree on rules. Message queues are like passing notes through a teacher. Slower, but the teacher makes sure everything stays organized and nothing gets lost.